Cigarettes—and smoking—are cool. Look at Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon sparking a cigarette with a touch-tip lighter and taking an effortlessly suave drag. That’s all the evidence you need.

Allow me to elaborate.

The artist—writer, filmmaker, musician, painter—is, by nature, an aesthete. Though we may not always care to admit it, our primary consideration is with appearances. Our eyes catch what is on the surface. Instinctual, gut-level reactions, unadulterated by the superego. When we stand in front of a painting, we embrace our emotional response. We do not wait for our mind to rationalize why we are drawn to certain colors or strokes of the brush. To understand the appeal of the cigarette, then, it is necessary to view the cigarette as art.

The aesthetic movement, according to the Tate, is “a late nineteenth century movement that championed pure beauty and ‘art for art’s sake’ emphasizing the visual and sensual qualities of art and design over practical, moral or narrative considerations.” Art is not interesting when it simply reflects a universal reality. You can marvel at a hyper-realistic portrait by Van Dyck or Reubens (as I often have and will continue to do), but there is something energizing about seeing a skewed depiction of reality, as in the paintings of Picasso or Dalí. The blatant disregard of reason is liberating. It is not practical. It is “art for art’s sake.”

What image does smoking project to society? Some might argue that it displays weakness, embarrassment, uncleanliness. Perhaps if you smoke hunched over, cowering in a corner far from the public eye, you may convey that unsavory image. If, however, you accept the cigarette as an extension of yourself, an outward expression of your personality, it assumes an entirely different set of attributes. Smoking is the ultimate nihilistic gesture. An indifference to life. Valuing aesthetic concerns over moral or practical ones.

In Cigarettes Are Sublime, Richard Klein sees the cigarette as more than just tobacco rolled into a paper cylinder.

Cigarettes are frequently signs, but especially ambiguous ones, difficult to read. The difficulty is linked to the multiplicity of meanings and intentions that cigarettes bespeak and betray; they speak in volumes, rather than in brief emblematic legends. The cigarette is itself a volume, a book or scroll that unfolds its multiple, heterogeneous, disparate associations around the central, governing line of a generally murderous intrigue. The cigarette is a thyrsus, the wand of Dionysus, which Baudelaire took to be the emblem of all poetic language, whose vine leaves are the poet’s fantasy and invention and creative purpose. Smoking there at the end of two delicately poised fingers or emerging from its pack at the end of an offer to smoke, the cigarette may convey worlds of meaning that no thesis could begin to unpack, that requires armies of novelists, moviemakers, songwriters, and poets to evoke.

Later, Klein examines cigarettes within the bounds of Freud’s pleasure principle. The principle suggests that the satisfaction of a desire erases the need for that desire (e.g. an infant suckling on a mother’s breast). Not so with the cigarette.

Cigarettes, however, defy that economy of pleasure: they do not satisfy desire, they exasperate it. The more one yields to the excitation of smoking, the more deliciously, voluptuously, cruelly, and sweetly it awakens desire—it inflames what it presumes to extinguish. The perversity of this excitation consists in the fact that it never sleeps and is never extinguished; it is removed from the economy of utility in which the expenditure of energy can be calculated, according to an equation of profit and loss. Filling a lack hollows out an even greater lack that demands even more urgently to be filled.

Cigarettes have no rational purpose. There is no logical argument for why to smoke or what advantages will be gained by smoking. Like art, cigarettes are about excitement and immediate, visceral reactions—the delicious, the voluptuous, the sweet desire. Smoking shirks the necessity of reason. The insouciance to convention, to the optimization of human life through scientific processes, establishes smoking as cool.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “cool” can be defined—for the purposes of our argument—as “not affected by passion or emotion, dispassionate; controlled, deliberate, not hasty; calm, composed” and (in relation to jazz) “restrained or relaxed in style.” The colloquial definition of “attractively shrewd or clever; sophisticated, stylish, classy; fashionable, up to date; sexually attractive” is perhaps most fitting for our circumstances. Really, it’s an amalgamation of all three. The cool person is never ill at ease, never in a rush. I once heard an anecdote about Jack Nicholson who told his co-star, when the two of them were late to a shoot, not to run because people would know they were late. Since then, I don’t run anywhere. Occasionally, I’ll ramp the pace up to a power-walk.

It is possible to smoke and lack coolness. Imagine the person sucking on their cigarette, failing to savor every puff, smoking with the neurotic fear that someone will steal their pleasure. One of the purposes of smoking is to express an indifference towards time. The cigarette is a timekeeper. A burning hourglass. The earth may continue to rotate and traffic may continue to stream through the streets, but I will stand here and smoke until the flame singes my cigarette down to a nub.

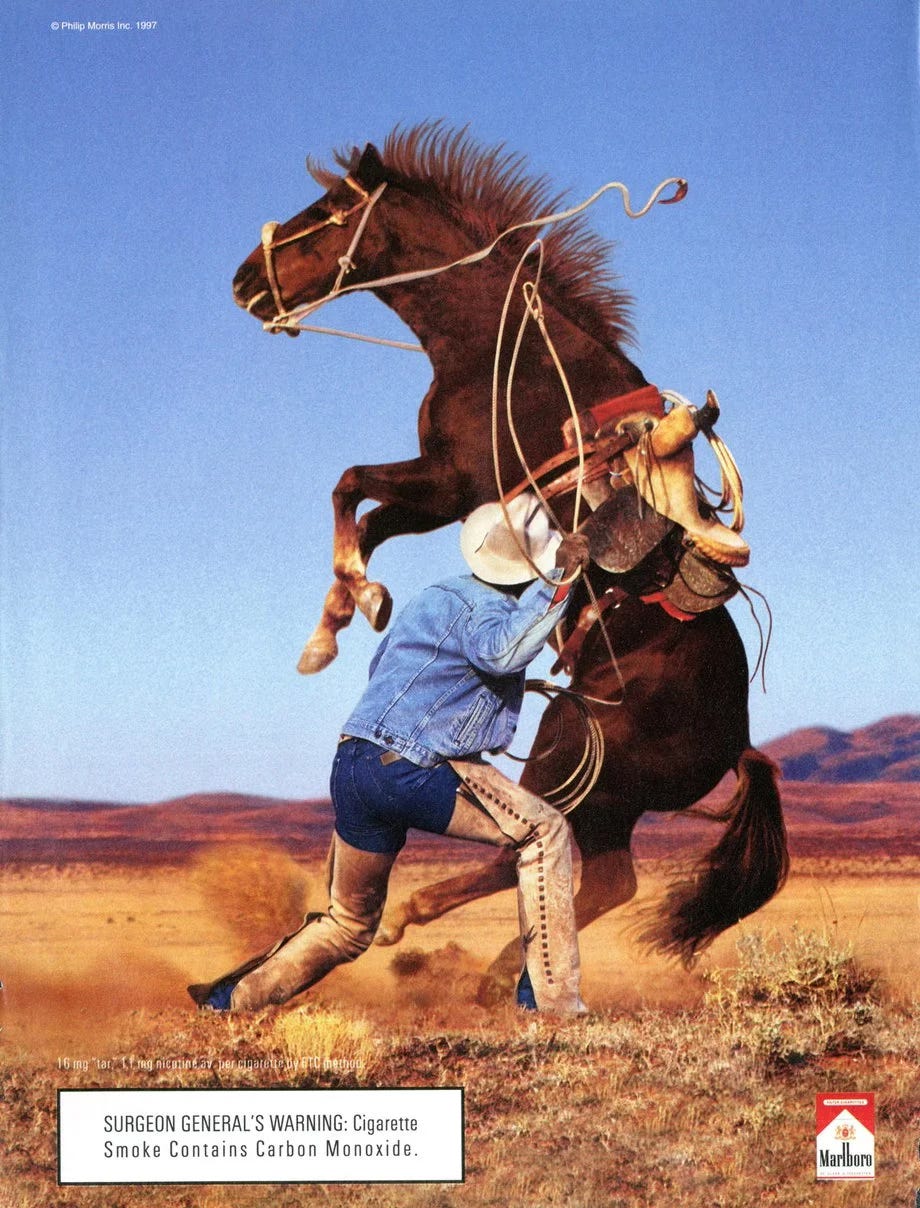

You know what else is cool? Vintage cigarette ads. Joe Camel. The Marlboro Man. So slick you can feel it oozing off the page.

Whatever side of the smoking argument you currently find yourself on, step back for a moment. Separate reality from art. It is impossible to track the link between cigarettes and the advancement of cool without understanding the role of smoking in film. Smoking as a character trait.

The greatest tragedy of Miami Vice was taking the cigarettes away from Crockett because too many young, impressionable viewers idolized his character. No parent wants their ten-year-old son asking to bum a cigarette. It’s a shame; I could have watched Don Johnson, in his pastel suits and loafers sans socks, smoke for hours. Imagine if they bowdlerized Mad Men in the same way. That’d be like eating an ice cream sundae without the ice cream.

J.J. Gittes in Chinatown. Mia Wallace in Pulp Fiction. Vincent Vega in Pulp Fiction (if you think he’s just a bumbling, twist-dancing hitman who gets himself killed for sitting on the toilet too long, you’re wrong). Marcello Rubini in La Dolce Vita. Michel and Patricia in Breathless. Any character in any Cassavetes film. Likewise, any character in any Scorsese film. Philip Marlowe in The Long Goodbye or The Big Sleep. Marla Singer and Tyler Durden in Fight Club. All of these characters exude cool.

David Lynch smokes, if you needed more evidence.

In high school, one of my teachers asked our class if smoking was a dealbreaker in a relationship. Everyone, including him, raised their hands. I didn’t. In fact, I considered it preposterous. Cigarettes are like sunglasses. They make almost everyone instantly more attractive. The quintessential “bad boy” archetype. That’s the official term, as coined by Carl Jung. We are attracted to things we deem dangerous. Our interests are piqued by the suggestion of risk.

Is it not the purpose of youth to live carefree and unconcerned with mortality, and to deal with the repercussions in our crippled, phlegm-hacking twilight years? Besides, the sheer stubbornness of our youth will overpower any subsequent sicknesses or ailments. Remember: cool people do not die uncool deaths.

Cigarettes, like eggs, are versatile things. Consider the many manners in which you can fondle a cigarette.

There’s the classic way, nestled between your index and your middle finger. Or the overhand grip, your middle, ring, and pinkie fingers canopied over the cigarette. The Michel Houellebecq method (barely caressed by the middle and ring fingers). For those wishing to avoid jaundiced fingers, try the classy style: the cigarette holder. The cigar hook. The options are limitless.

Here is a picture of JFK smoking:

A collection of quotes about smoking:

“I know I don’t smoke. I don’t inhale because it gives you cancer. But I look so incredibly handsome with a cigarette that I can’t not hold one.” - Woody Allen, Manhattan

“Cigarettes and coffee, man, that’s a combination.” - Iggy Pop, Coffee & Cigarettes

“The beauty of quitting is, now that I’ve quit, I can have one, ‘cause I’ve quit.” - Tom Waits, Coffee & Cigarettes (a film called Coffee & Cigarettes deserves at least two mentions)

“Smoking is one of the greatest and cheapest enjoyments in life, and if you decide in advance not to smoke, I can only feel sorry for you.” - Sigmund Freud (again, this is in reference to cigars, but tomayto, tomahto)

“I quit smoking in December. I’m really depressed about it. I love smoking, I love fire, I miss lighting cigarettes. I like the whole thing about it, to me it turns into the artist’s life, and now people like Bloomberg have made animals out of smokers, and they think that if they stop smoking everyone will live forever.” - David Lynch

Is this an unnecessarily lengthy defense of the cigarette? Yes. Given that I don’t smoke myself, it’s even more absurd. And, given the widespread knowledge about the motley of diseases and painful deaths engendered by smoking, it’s triply absurd. But if you really believe that, you didn’t pay attention to my spiel.

Why do smokers smoke? What compels them to pick up that first cigarette? The nicotine addiction doesn’t kick in until the smoking becomes a veritable habit. They pick it up because they see their friends doing it, because it looks cool, and because it symbolizes a stress-free life. No one smokes because they’re hoping to gain some personal advantage. It won’t raise your IQ or make you a faster runner or get you a raise at work. I suppose the question is, then, should you smoke?

Take a few minutes and ponder it over your next cigarette.

Please note that this post is not responsible for any relapses or new smoking habits. It will, however, gladly accept credit for any levels of cool attained.